|

趙耶利彈琴之法

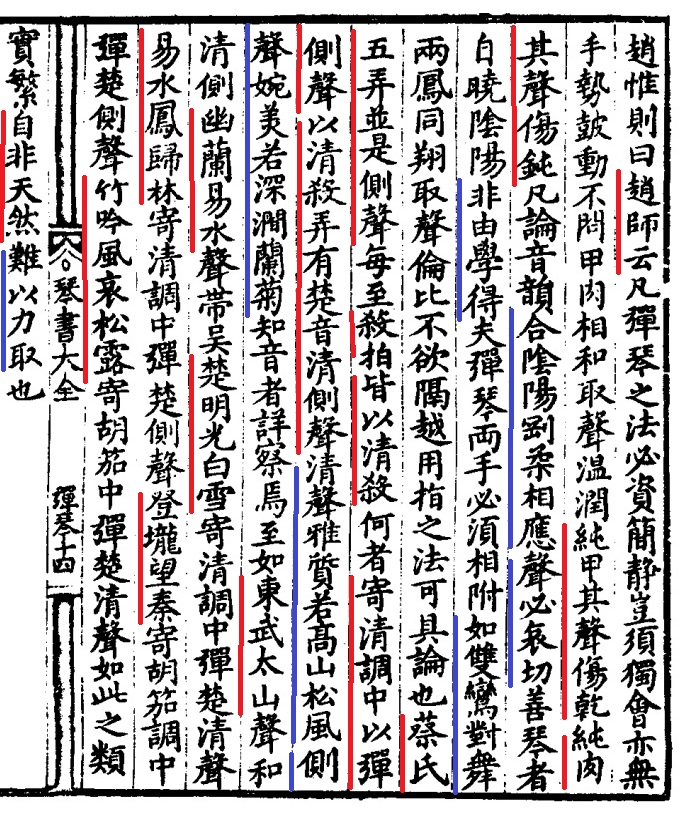

吳聲清婉,若長江廣流, 繇延徐逝,有國士之風。 "The sounds of the Wu [school] are limpid and sweet like a vast and long river flowing slowly, like the demeanor of talented scholars. The sounds of the Shu [school] are agitated like impetuous waves or a sudden thunder, that's another outstanding style of the time." (translated by Luca Pisano from Zhu Chang Wen's [Qin Shi] 朱長文[琴史]) Zhao Yeli's discussions on qin playing found in "琴書大全" (Complete Collection of Qin Scores) compiled by Jiang Keqian in the Ming dynasty: Master Zhao Yeli once expressed that in the art of playing the qin, one must embody the qualities of simplicity and tranquility. How can one play without attending to the coordinated movements of both hands and overlooking the harmonious collaboration between fingernails and finger flesh, which contributes to producing a warm and resonant sound? Using only fingernails results in a dry sound, while relying solely on finger flesh produces a dull sound. When delving into musical tones, one must adhere to the principles of yin and yang, combining strength and flexibility, mutually harmonizing. The resulting sound will naturally be profound and moving. Those skilled in playing the qin naturally grasp the principles of balancing yin and yang. This understanding isn't acquired through formal learning. When playing the qin, both hands must cooperate as if two phoenixes are dancing together. They soar in unison, equal and harmonious, without surpassing or hindering each other. The techniques of using the fingers in qin playing can be discussed in great detail. Cai Yong's "Five Nong" (5 qin pieces) are all played with a Cè Sheng (lateral sound). At the ending, a Qing Sheng (Peiyou note: In Chinese music theory, 清聲 Qīng Shēng can be interpreted as either one octave higher or half a pitch higher.) is employed. Why is this? It is to integrate the Cè Sheng (lateral sound) within the Qing Diao (Qing mode,) using the Qing Sha (Qing Sheng for the final coda) and thus creating Qing and Cè sound of Chǔ. The Qing Sheng is elegant and distinctive, possessing substance, akin to the wind rustling through pine trees on high mountains. The Cè Sheng is graceful and beautiful, evoking the imagery of orchids and chrysanthemums in the deep mountain valleys. Those who comprehend the nuances of sound should keenly appreciate this. As for the music of [Dong Wu Tai Shan,] it employs Qing and Cè Sheng, while [Yolan] and [Yi Shui] incorporate elements of the Wu (area) sound. [Chǔ Mingguang] and [Bai Xue] borrow the Qing mode and play the Chǔ Qing Sheng in it. [Yi Shui] and [Feng Gui Lin] borrow the Qing mode and play the Chǔ Cè Sheng. [Deng Long] and [Wang Qin] borrow the Hu Jia mode and play the Chǔ Cè Sheng. [Zhu Yin Feng] and [Ai Song Lu] borrow the Hu Jia mode and play the Chǔ Qing Sheng, among others. In reality, complexity does not come naturally; it is challenging to achieve through force alone. (Translated by Peiyou Chang) Original Chinese text: (原文)

| |||||||