|

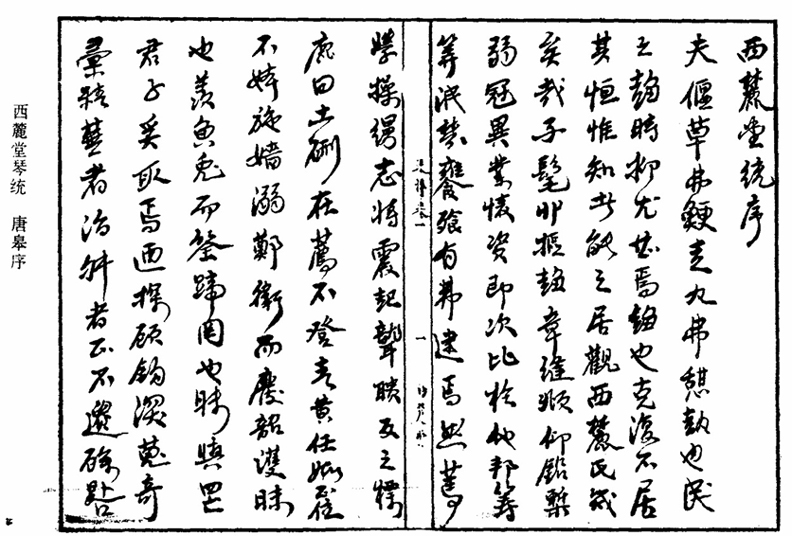

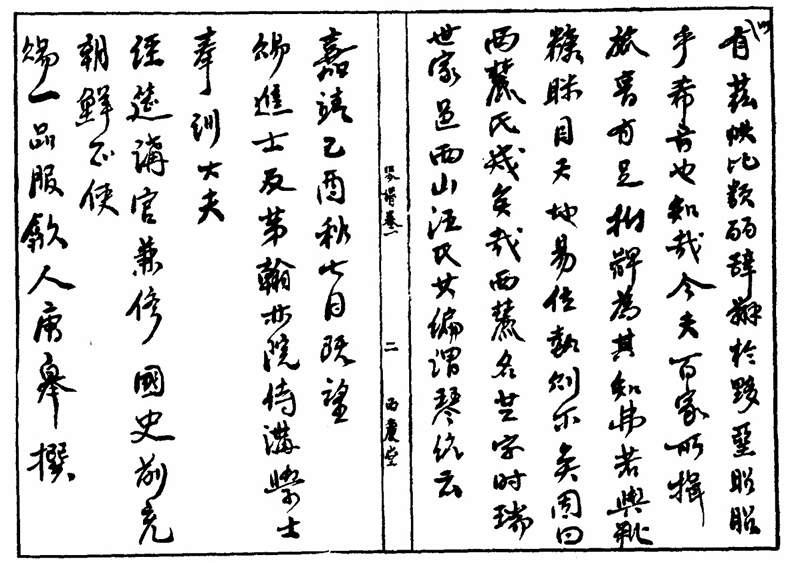

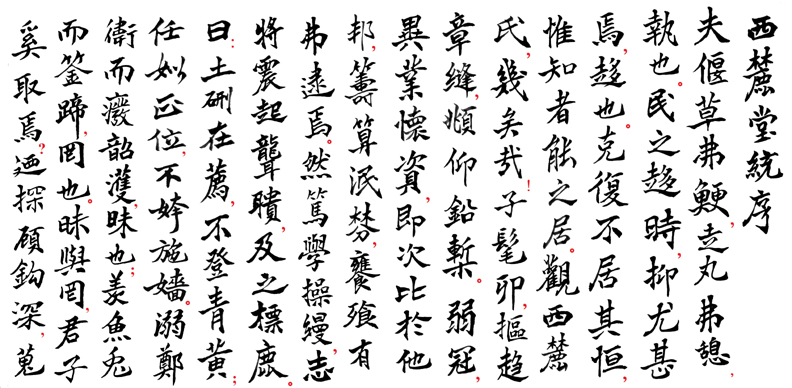

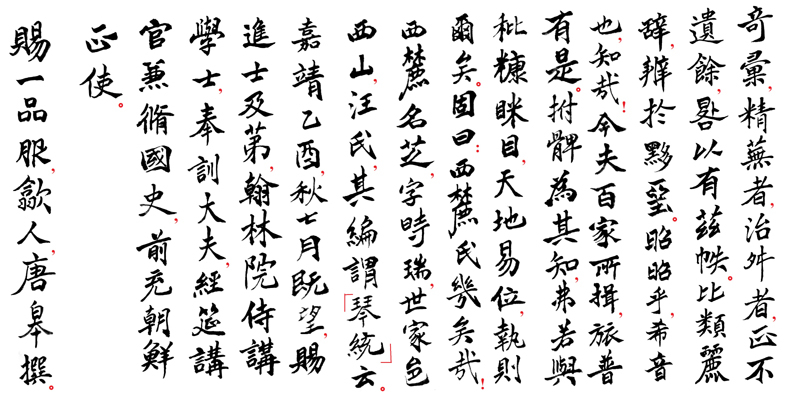

唐皋〈西麓堂琴統〉序之翻譯   The Challenges of Studying the Texts in Xīlùtáng Qíntǒng, Including Táng Gāo’s Preface Studying the essays in Xīlùtáng Qíntǒng presents considerable challenges for several reasons. First, the text is handwritten rather than printed, and some characters are difficult to decipher due to illegible handwriting. Second, the absence of punctuation requires the reader to carefully determine appropriate pauses and sentence boundaries. Third, the text employs many archaic grammatical structures and vocabulary, which are rarely encountered in modern usage, making comprehension particularly difficult. Additionally, the Chinese language’s use of single characters with multiple meanings necessitates close attention to context. This often requires consulting the Cíhǎi dictionary and other specialized resources to accurately interpret the meanings of words and sentences. Resources consulted include: 1. Shū Xīnchéng et al., Cíhǎi (Combined Edition) (Hong Kong: Chung Hwa Book Co., 2000, 2nd ed.). 《辭海》(合訂本),舒新城等編著(香港:中華書局,2000,第二版)。 2. Complete Table of Standard Cursive Script Representative Symbols – Based on the 10th Edition of Standard Cursive Script, with reference to the Standard Cursive Script Lexicon compiled by Hu Gongshi; initial draft by Liao Zhenxiang. (Year of publication unknown) 《標準草書代表符號一整表 — 參照標準草書第十次本,胡公石編著〈標準草書字彙製表〉,草擬者:廖禎祥初稿》。 3. Leon Long-Yien Chang and Peter Miller, Four Thousand Years of Chinese Calligraphy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990). 4. A Dictionary of Cursive Calligraphy from Renowned Calligraphers 集大家書法草書書法字典 (https://app.6z6z.com/post/) 5. Revised Mandarin Dictionary (Re-edited Edition), National Academy for Educational Research, Taiwan. 《重編國語辭典修訂本》,台灣國家教育研究院。 Available at: https://dict.revised.moe.edu.tw/index.jsp If there are any shortcomings in my interpretation, I sincerely welcome feedback and guidance from those more knowledgeable. Rewrite in Standard Kaishu style with punctuations In order to better understand the text, I rewrote it in standard Kaishu (楷書) style with punctuation.   白話文 草隨風而倒伏,不再直挺,是順從的,不抗拒的,走動的圓珠不會停歇,這是貫性的原因;人們追逐時勢和潮流,而且這種行為甚至達到過分的程度,顯示出一種盲目跟風,急於迎合的特性。克己復禮之道難以持久,唯有真正有智慧的人才能安於其位,做到恆久不變。看看西麓氏,他就是非常接近這樣品質的人了。 他年輕時(鬌髮開始覆蓋額頭時)(提起衣襟)恭敬研讀儒家學說,抬頭低頭勤於寫作校勘文章典籍。二十歲時,他懷有才學與抱負(或懷著一筆資金),選擇了一條不同於常人的道路,便是到他鄉工作,然而生活中的種種籌劃與算計常常一團混亂,不是一個會精打細算的人,吃飯問題也未能完全解決。 然而,他執著於學習,專心於琴道的研習與實踐,立志要喚醒那些耳聾目閉、不明事理的人以追趕上太古時期。他說:「古(周朝的禮樂)典範已被呈現出了,但青(新秧)黃(熟穀)卻不成與匱乏 (象徵著未實現的德行);賢德的任母后與姒母后各自居於正位,不夸美西施與毛嬙。那些沉溺於鄭衛之音而拋棄正統韶濩之樂的人,終究只是在黑暗中徘徊;那些因喜愛而渴望獲得魚和兔子並用網子及捕兔器去捕捉的人,是迷茫的。昏暗和迷惑,君子怎能接受呢?」(以上所說乃在形容尊古崇賢而不惑於外表的美麗)於是,(汪芝)探究深奧的理論,蒐集尋找不尋常且優良的彙編,精雕細刻那些繁雜的,修正那些錯誤的,一點也不遺漏,做到盡善盡美。經過長久努力,才編纂出了這套《琴統》。 他將相關的理論進行類比整理,文字優美,分辨黑白對錯,既明白又清楚,真是稀有且卓越的聲音,無疑是智慧的結晶!如今,我們看到許多人所高度推崇的(琴學知識),無處不在。(人們)拍著大腿,為他們所知讚歎不已. 不就是同於那些讓人眼花繚亂而令人困惑的思想,甚至天地倒置顛倒是非,如此執著罷了. 因此說:「西麓先生確實是少有的了不起!」 西麓先生名為汪芝,字時瑞,世居徽州府歙縣西山。他的著作名為《琴統》。 嘉靖己酉(應為乙酉年 西元1525年 見註6)秋七月既望(十六日),由賜進士及第、翰林院侍講學士、奉訓大夫、經筵講官兼修國史,並曾出使朝鮮,被賜予一品服飾的歙縣人唐皋撰序。 Translation When grass bends, it does not resist, and when a ball rolls, it does not pause—such is the nature of steadfast adherence. Yet people, in their pursuit of trends and conformity to the times, do so to an excessive degree, driven by the need to follow. The path of self-discipline and returning to ritual is difficult to sustain; only those with true wisdom can be at peace with their position and remain steadfast without change. Look at Xīlù; he is one of the few who is able to achieve this. When his hair began to cover his forehead (marking the age of youth), he respectfully and devoted himself to studying Confucian teachings. Bowing over and raising his head from the writing desk, he diligently engaged in writing and studying texts and classical works. At the age of twenty, though he possessed both talent and ambition (or he possessed a sum of money), he chose a path different from most, leaving his hometown to venture into distant regions. However, his plans often ended in confusion (he was not adept at careful budgeting) and he struggled to secure even his daily sustenance. Yet he was devoted to diligent learning and disciplined qin practice, aspiring to awaken those deaf and blind to reason and help them catch up to the ideals of antiquity.(*1) He declared: "Worthy ancient models (*2) are put forward, yet green and yellow grains remain unharvested (symbolizing unfulfilled potential or scarcity); the virtuous Queen Rèn and Queen Sì (*3) hold their rightful positions, without favoring the beauties like Xī Shī and Máo Qiáng. (*4) Those who indulge in the frivolous sounds of Zhèng and Wèi, abandoning the orthodox Sháo and Hù music, are lost in darkness. Using traps and nets solely out of a desire to catch fish and rabbits is an act of delusion. Darkness and delusion—how could a noble person accept such things?"(*5) Thus, he delved into profound theories, sought out and compiled exceptional and uncommon works, meticulously refined the intricate, corrected the erroneous, and left nothing overlooked, striving for perfection. After prolonged and arduous effort, he finally compiled this collection. He draws analogies and organizes the relevant theories with elegant writing, clearly distinguishing between black (wood) and white (earth)(*6). It is crystal clear—truly a rare and exceptional voice, undoubtedly the result of profound wisdom! Nowadays, the knowledge esteemed by various schools is widespread. People slap their thighs in admiration, yet this so-called wisdom is as bewildering as chaff (worthless stuff) blinding the eyes, or heaven and earth being overturned. If one clings to it, this is what it leads to. And so they exclaim: 'Mr. Xilu is truly remarkable and rare! Xīlù, whose personal name is Zhī and courtesy name Shíruì, belonged to the esteemed Wāng family of Xīshān (Western Hill). His compilation is known as Qín Tǒng (Qin Anthology). On the sixteenth day of the seventh month in the autumn of the Yǐ Yǒu year of the Jiājìng reign (1525 instead of 1549 CE *7), a preface was written by Táng Gāo of She County, a Jìnshì laureate appointed by imperial decree. Táng Gāo also served as an Scholar-in-Attendance at the Hànlín Academy, an Instructor Gentleman by imperial appointment, a scholar official at court banquets, and a compiler of national history. He was once sent as an envoy to Korea and was bestowed first-rank attire.

註(*1) 標鹿 (biāo lù): "Treetop" (biāo) and "wild deer" (lù). This metaphor represents the simplicity and harmony of ancient times. The phrase originates from Zhuāngzǐ (Heaven and Earth), which states:

Conclusion

In this essay, Táng Gāo presents Wāng Zhī (Xīlù) as a man of remarkable self-discipline, wisdom, and intellectual integrity. Deeply committed to Confucian ideals, Wāng Zhī remained true to his principles despite early-life confusion and persistent hardships. Postscript |