|

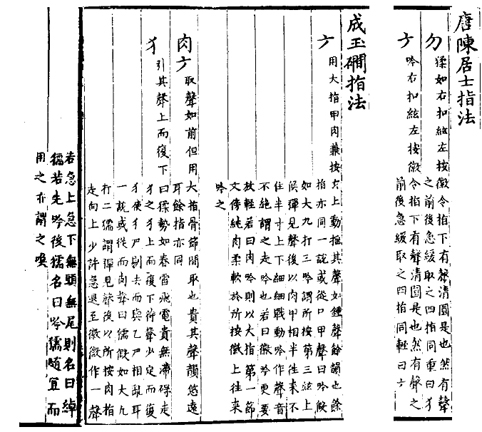

Yín and Náo are the 2 important left hand techniques of Gǔqín playing but some people may not clearly distinguish the differences. I have checked many qín books and the explanations vary such that I am not sure which one to follow. Therefore, I decided to only look at the possible earliest records and hope to get more ideas on how the ancient qín players distinguished them. The earliest records so far that has the Gǔqín left hand technique explanations of Yín 吟and Náo猱 are those from the Táng dynasty and Sòng dynasty, such as Táng, Chéng Ju-shì 陳居士 and Chéng Zhúo 陳拙 and Sòng, Chén Yù-Jiàn 成玉礀 . I paste their quotes here which are collected in the very rich qín book [Qín Shu Dà Quán 琴書大全] edited by Míng dynasty Jiăng Kè Qian 蔣克謙, along with my translation and conclusions below.

The explanations of Yín and Náo from Chéng Ju- shì is very simple compared to the other two people. My translations are as below. Náo: If the right hand pluck a string, the left hand presses down the string on a hui position and under the left finger, the string has sound, and the sound is clear and rounded. However, this sound has its variations by producing it earlier or later and faster or slower. All the 4 fingers are the same. If produced heavily, we called it Náo. Yín: The explanation of Yín is the same as above, except that at the end, it says, if produced lightly, we called it Yín. Conclusion: It does not really tell us what exactly the techniques are, but tell the colors of the sound – heavy, light, clear and rounded. My translation of the explanations of Yín and Náo from Sóng dynasty Chén Yù-Jiàn , are as below: Yín: use the left thumb where the nail and the muscle meet (on the right side of thumb nail) and press down a string and swing it. The sound is like a leftover sound reverberation from a bell. The rest of the fingers are the same. Another saying is that maybe only use nail and that is called Yín. For example, left thumb presses down on the 9th dot and the right hand plucks the 3rd string then Yín, which means once the 3rd string is plucked, use the area where the nail meets the muscle and move back and forth without stopping, and the distance is half an inch up then down, very tiny swinging (vibrato). When the vibrato is not stopping, it is called walking Yín (走吟 walking vibrato). If it is called “slight vibrato” (微吟), one must do it in a very relaxed manner. If it is called “muscle vibrato” (肉吟), only use the side muscle of the thumb joint, and softly make the vibrato on a hui position. Rò Yín (muscle vibrato): same as above, produced from the side of thumb joint. Valuing its finals and reverberation distance. Náo: Stretch the sound by going up and down called “Náo”. The momentum is like spring thunder and flying lightning, valuing its smooth movement without any hesitation. “Walking Náo” (走猱) is that the up and down movement produced and the sound is created, then wait for about a second and do the up and down movement again. Another saying is that the Náo (the Chinese character here changes to 犭需 which is pronounced Ró) is using muscle instead of nail. For example, Dà Jiŭ Dă Èr Ró (thumb pressed down at 9th dot and right hand plucked 2nd string and Ró) means when the string is plucked, move the thumb by using its right side of the joint muscle, up a little bit and then rapidly move down to the hui position, slightly make one sound. If rapidly move up and down without heading and ending, it is called “Chuò Ró” (綽犭需). If doing Yín first then doing Náo later, it is called Yín Náo (or Yín Ró 吟犭需), also called “Huàn” (喚). Which to use is all depending on its appropriate situation. Conclusion: From Chén Yù-Jiàn‘s explanations, it is still unclear but one can find some clues. First, using nail or muscle, my experience of qín playing tells me that only the thumb has this issue. The rest of the left fingers don’t have this concern. Therefore, I don’t think it is an appropriate point to distinguish the technique of the Yín and Náo. 2nd, From the following two sentences, one can clearly tell the quality of the Yín and Náo:

The sound is like a leftover sound reverberation from a bell. --- Yín 3rd, from the actual technique: the sentence for Yín “…move back and forth without stopping, and the distance is half an inch up then down, very tiny swinging (vibrato).” And the sentence for Náo “Stretch the sound by going up and down …up a little bit and then rapidly move down to the hui position…” Combining the 2nd and 3rd points above, the up and down movement of Yín is not as wide as Náo but is more frequent than Náo. Yín has an even strength (in up and down), but the Náo starts light and ends heavily (in up and down). Imagine hearing the sound of spring thunder that starts soft but ends loud, and the line of a lightning is not as smooth as a water wave.

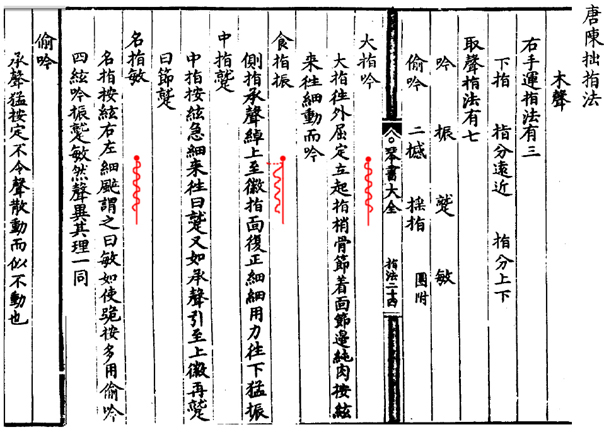

Below are the explanations from Táng dynasty, Chéng Zhúo.  For “Yín”, Chéng Zhúo noted at the end of the explanation of the ring finger’s “Yín” that each finger (thumb, index, middle and ring) has a different name but the theory is the same. 四絃吟振蹵敏 然聲異 其理一同. Thumb “Yín”大指吟: Use the side muscle of the thumb joint to press down a string and slightly rub it back and forth. Index Finger “Zhèn” 食指振: Starting with the left side of the index tip slide up to a hui position then turn the tip to face down on the string and quickly vibrate the string. Middle Finger “Cù” 中指蹵: When the middle finger presses down a string, immediately vibrate the string back and forth quickly and delicately, and that is called “Cù”. If starting with sliding up to a hui position then vibrating the string, it is called “Jié Cù” 節蹵. (“Jié” has a meaning of “then” or “ following with”). Ring Finger “Mǐng” 名指敏: Press down a string, and then vibrate the string right and left (back and forth) delicately, that is called Mǐng. If using the kneeling down position (跪指) then the vibrato is called “Tou Yín” 偷吟, which means that it is a stable movement; you can hear the sound but you don’t see the finger moving back and forth. (“Tou” has a meaning of secretly.)

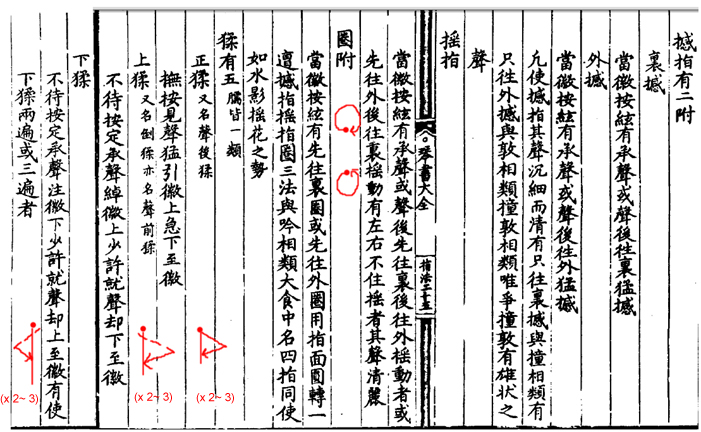

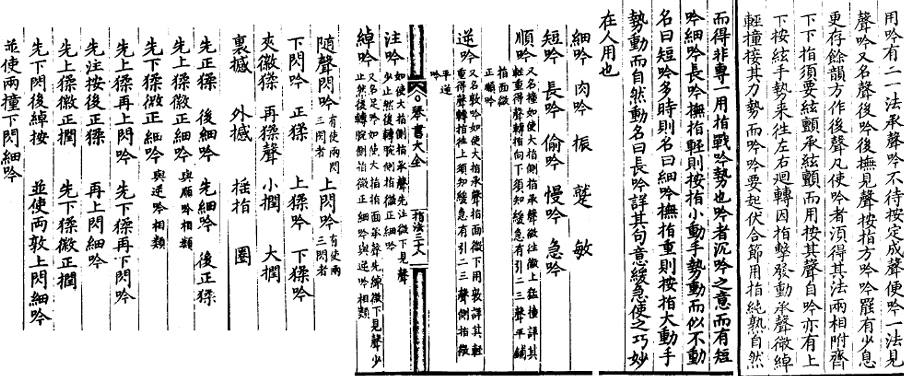

There are three more vibrato techniques similar to Yín: Hàn Zhǐ 撼指, Yáo Zhǐ 搖指and Quan Fù 圈附. At the end of “Quan Fù”, Chén-Zhúo noted that these three techniques are similar to “Yín” and are useful for all 4 fingers. It is like the gesture of a reflection of a swinging flower on the water. “Hàn” literally means to shake. There is inside Hàn 裏撼and outside Hàn 外撼. Inside means the right side of your left hand and outside means the left side of your left hand. (Imagine that your body is the center, so anything towards the center is called “in” and outwards from the center is called “out”.) This Hàn vibrato can happen simultaneously when the sound is created or half of a second after the sound has been created. It is a delicate vibrato which is similar to “Zhuàng 撞” (an inward strike-against, also called “Shùn Yín” 順吟) and “Dun 敦” (an outward strike-against, also called “Nì Yín” 逆吟), however, Zhuàng and Dun are more powerful than Hàn. The sound quality of Hàn is profound yet clear. “Yáo” literally means to swing. It also can be produce simultaneously when the sound is created or half of a second after the sound has been created, and can start the swing inside out or outside in. The sound quality is clear and pretty. “Quan” literally means circle. “Quan Fù” is the movement of making an inward circle or outward circle. So my understanding of Quan Fù is the making of a circling vibrato. So, all the above techniques are the variations of the “Yín”. For “Náo”, The Chinese character of Náo 猱, and the character of Ró臑, both have the same meaning of the Náo technique, which is a strong upward and a rapid downward movement that happens right after the sound has been created, (the direction of “up” is the right side of the qín player, and “down” is the left side of the qín player). This movement can be done two to three times. There are 5 kinds of Náo: 1) Zhèng Náo (正猱, Zhèng literally means major or straight) also named Sheng Hò Náo (聲後猱, Sheng Hò literally means sound after). When the string is pressed down and plucked, the left hand strongly slides up to the right side of the hui position and rapidly slides down to the hui position. 撫按見聲猛引徽上急下至徽 2) Shàng Náo (上猱, up) also called Dào Náo 倒猱 (invert) or Sheng Qían Náo 聲前猱 (before sound). When the left hand presses down a string, and the right hand plucks the string, simultaneously and without any stopping, the left hand keeps sliding up to the right side of the hui position, and then slides down to the hui position. (the sliding up movement is using the technique of chùo綽)不待按定 承聲綽徽上少許 就聲卻下至徽 3) Xià Náo (下猱, down) . Same technique as above but in the opposite direction. When the left hand presses down a string, and the right hand plucks the string, simultaneously and without any stopping, the left hand keep sliding down to the left side of the hui position, and then slides up to the hui position. (the sliding down movement is using the technique of Zhù 注) 不待按定 承聲注徽下少許 就聲卻上至徽. This up and down movement can be done two to three times.

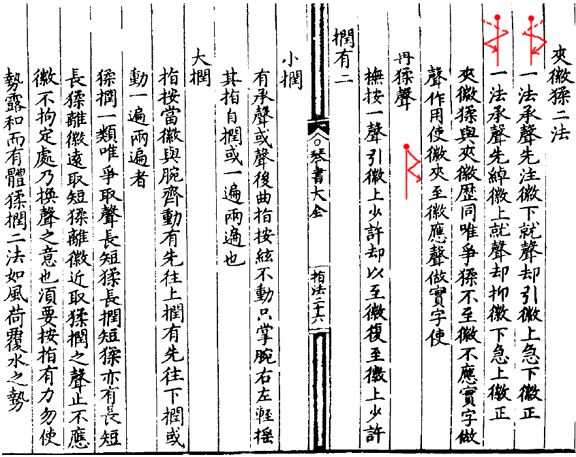

4) Jía Hui Náo (夾徽猱, Jía literally mean “Press from both sides”): Also has two opposite directions. A is zhù xià (注下, glides down from the right side of the hui position to the left side of the hui position) then Yǐng shàng (引上 slides up to the right side of the hui position) and then jí xià (急下 rapidly slides back down to the hui position). B is chùo shàng (綽上 glides up from the left side of the hui position to the right side of the hui position), yì xià (抑下 slides down to the left side of the hui position) and then jí shàng(急上 rapidly slides back up to the hui position). The movements can be like the red lines I had draw in the pictures. (for chùo and zhù, please click here). 5) Zaì Náo Sheng (再猱聲, Zaì literally mean “again”.) When the sound is produced, the left hand slides up from the hui position to the right side of the hui position and then slides down to the hui position and then slides again up to the right side of the hui position. Ruèn (潤, this character has the meaning of moisten, touch up or smooth), this technique is that your finger does not move but the palm slightly swings right and left. The difference between Náo and Ruèn is that Náo is longer and Ruèn is shorter. However Náo has the longer Náo and the shorter Náo as well. The longer Náo means to stretch the sliding up or down further, and the shorter Náo is that the stretch is shorter. And sometimes the Náo and Ruèn techniques do not stop exactly at the hui position. It can be stopped anywhere. And the last sentence here says :猱潤二法如風荷覆水之勢 which gave us a good picture to imagine what these movements look like. They are like the wind blows on the surface of a water lily.

From the above picture, Chéng Zhúo explained more about the “Yín” and the different combinations of Yín, Náo, and Ruèn. I am concluding his major points as below, the rest then is all up to the qín player’s own interpretation: When to start the vibrato – (1) immediately when the sound is created, or (2) a half second later when the sound has created. After a Yín is created, wait a little bit to hear the reverberation, and then continue to play the new note. Hand gestures – the left hand rubs the string up and down (right and left, back and forth) or circling. How strong – depends on the relationship with the strength of the right hand plucking and the strength of the previous movement which could be, for example, a gently sliding up or a lightly strike-against, then continuing with the vibrato. It has to be natural, reasonable and well trained. Do not separate the vibrato itself as a single movement and reinforce it from the rest of the playing. If the plucking was light, the vibrato has to be a small movement, and the hand gesture is not showing the movement obviously but essentially. That is called a short Yín (Duǎn Yín 短吟). If it is a small movement with many repetitions, it is called a delicated Yín (Xì Yín 細吟). If the plucking is heavy, the vibrato has to be a big movement, and the hand gesture is showing the movement, which is a natural movement; it is called a long Yín (Cháng Yín, 長吟).

How to distinguish and apply – Read carefully the music piece and understand the feeling then practice well. How to distinguish the variety of Yín (or any other techniques) and use them properly, is all by the interpretation of the qín player himself or herself. Many ancient qín tabletures do not indicate specifically which kind of Yín or Náo to use. Some might indicate with the combination of up or down, slightly or long, etc., but most of the time, it only shows a single character of Yín or Náo. So the qín player has to refer to the previous note or the following note and the feeling of the music and then make his or her own judgment and interpretation.

| ||||